Remember Together: Nuclear Test Veterans A Reminder of Our Nuclear Past

By Eva Jones

Student Eva Jones, recounts the event she attended on ‘Remember Together: Nuclear Test Veterans’, a commemorative project that captures the important experiences of four Nuclear Test Veterans from Britain and Fiji.

In 2022, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced that the country’s nuclear test veterans were to be honoured with a medal in recognition of their contributions to Britain’s nuclear testing programme in the 1950s and 60s. The testing programme, which comprised of dropping 45 nuclear bombs across Australia, Kiritimati (Christmas Island), other Pacific islands, and the United States, included the participation of around 22,000 British men and women. Today they are known as nuclear test veterans (NTVs); the long-unrecognised people whose contribution to the success of Britain’s atomic testing programme, which ranged from clearing nuclear debris to clerical jobs, has remained widely unheard of. That is why Big Ideas, funded by the Office for Veteran Affairs, have created ‘Remember Together: Nuclear Test Veterans’, a commemorative project that captures the important experiences of four NTV’s from Britain and Fiji.

‘Remember Together: Nuclear Test Veterans’ was produced with the intention of broadening public understanding of Britain’s nuclear past and increase general engagement with the NTV’s who were actively involved in it. The project prioritises the personal stories of four NTV’s: Brian Davies, John Folkes, David Whyte, and Mr Naikawakawavesi. On March 21st I attended their online event for the students and faculty of the University of Liverpool and the University of South Wales, two universities currently collaborating to create ‘An Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans’, an ongoing online archive of life histories as told by forty NTV’s. However, ‘Remember Together’ strives to bring nuclear history to a primarily younger audience and to do so they conducted their interviews with Davies, Folkes, Whyte, and Naikawakawavesi through an intergenerational approach, allowing teenagers to lead the conversation with the NTV’s. This method was particularly effective in contrasting the innocence of the young, who have never witnessed an atomic detonation, and the almost reminiscing tone of the four gentlemen recalling their past experiences with Britain’s nuclear test programme.

The event began with Dr Virginia Crompton introducing the project, its aims, and their determination in ensuring that the authentic voices of the test veterans are heard. It was this unique focus on personal testimony which drew me to the event. For us today, understanding the physical and psychological implications of atomic weapons is confined to film screens or told in the pages of a book, but hearing the men talk briefly about their lives in relation to the nuclear tests humanised this aspect of British nuclear history. This was evident from the get-go, which began with the story of Brian Davies.Witnessing The Bomb

Brian Davies lives in South Wales and joined Operation Grapple at Christmas Island, in the Pacific Ocean, in 1958 at 18 years old. After being flown over in a luxurious airplane and remembering the non-caring nature of everyone on board, he stated that his first impressions of the island was both of fright and joy. I was immediately struck by his recollection of the smallest and most ordinary details, like the bug bites he received because they had to sleep in tents. Collaborating with teenagers meant that the questions asked allowed for a more authentic conversation and so they asked about everyday activities, including football, which Davies’ recalls playing with his fellows and against the RAF. The way in which he spoke about these memories in a warm manner contrasted with an underlying sense of danger, particularly when he discussed witnessing the nuclear explosion. For instance, it was shocking when he stated that they were lying on the beach, thirteen miles from the blast, completely unprotected and how he was consequently left covered in blisters from the searing heat and radiation. His account is a reminder of the dangers of nuclear weapons, especially to health, but also that those involved in the testing programme were ordinary people and still participated in day-to-day activities despite, in hindsight, the significance of atomic tests.

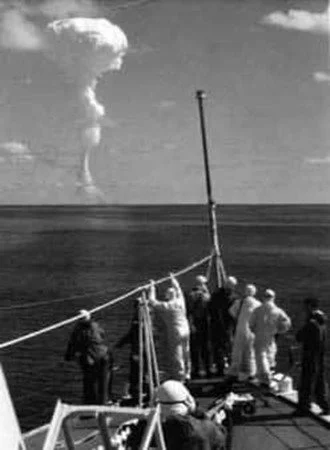

Christmas Island [Operation Grapple, Credit: BNTVA: the Charity for Atomic Veterans]

Flying Through The Mushroom Cloud

The second film shown was John Folkes’ story. His film in particularly has stuck with me since the event. When Folkes was a boy during the Second World War, he heartbreakingly lost his best friend during an airstrike on the way to school. However, he volunteered to join the nuclear test programme in Australia in 1956 when he was 19 years old. Astoundingly, Folkes has flown through a mushroom cloud and was given the task of taking radiation readings during nuclear explosions. Unlike Davies, Folkes seemed to look at this part of his life with more despair rather than fondness. He described how he was in aircraft five miles from the drop zone of the bomb, which is incredibly dangerous, and was told take his shirt off and hold it against his eyes. The bright light of the explosion was so strong that he recalls being able to see the bones in his fingers, and the intensity of the heat which made him flinch. Unsurprisingly, he stated that he’s plagued by nightmares from his time in Australia, which is especially sad as it’s been 68 years since the nuclear tests. I was left in disbelief when he mentioned that he was still proud of the work he and his fellow NTV’s undertook “in defence of [their] own country.” It’s for this exact reason – the sacrifice for patriotic duty – that NTV’s deserved to be celebrated and recognised for the risks they took for the country’s security.

John Folkes flying near the mushroom cloud, credits: Big Ideas, ‘Remember Together: Nuclear Test Veterans.

David Whyte

Scottish veteran David Whyte was the subject of the third film. Wearing his military cap and medals, Whyte discusses how he was sent to Christmas Island, like Davies, when he was just 20 years old. He described the island as a “tropical paradise” with its warm climate and “lovely area”. Unfortunately, the island was to be used to test the hydrogen bomb, the more powerful successor of the atomic bomb, which would devastate the islands natural beauty and indigenous population. Whyte witnessed 5 nuclear explosions during his time in the Pacific and although he was responsible for clearing atomic debris, he was provided with no form of protection from the radiation he was exposed to. I was astounded at how every testimony referenced the lack of protective equipment which left everyone involved in the nuclear tests extremely vulnerable. A thought which Whyte himself touched upon as he couldn’t understand why he was “sent into the danger area.” Yet, like his fellow NTV’s, Whyte felt a sense of pride of the work that he did.

“I’ll show you the way forward from my footprint.”

Naikawakawavesi, unlike the three previous interviewees, is from Fiji. Fiji, a previous British colony, was called upon to send their soldiers to Christmas Island to aid the British with the atomic test Operation Grapple. Naikawakawavesi was sent to the island in 1957, along with 300 other Fijian soldiers, to assist with the construction of various buildings for the British troops. Today he is 85 years old, and looks back at his history with the nuclear testing programme with a faint sense of nostalgia. I especially liked how he recalled spending his free time having picnics across the island! Nevertheless, he witnessed three atomic bomb explosions and his account of hearing the countdown, seeing the mushroom cloud, and subsequently feeling the searing heat 10 miles away from the drop zone was captivating. It was one of his final sentences of the interview which has stuck with me: “I’ll show you the way forward from my footprint.” He was referencing the project’s shared goal that we can teach the younger generation to learn from the mistakes of the past.

The final part of the event was interactive as we were encouraged to take part in a short quiz on Britain’s nuclear test programme. While I didn’t perform very well myself, it was a nice way to end the afternoon. We were also encouraged to write (or asking Dr Crompton to write on our behalf) a short message of support to the nuclear veterans. I found this to be a touching part of the event and encouraged all of us to really think about the significance of the stories we had just heard. Overall, it was a highly enjoyable and thought-provoking occasion, which has since left me thinking about the legacy of Britain’s nuclear programme and the test veterans’ emotive stories which remind us of our nation’s forgotten past.

Life History Interviewing: An Overview

In conducting our oral history interviews, An Oral History of Nuclear Test Veterans will use a life history approach. We aim to conduct interviews with forty British nuclear test veterans, covering all major test operations and services, with the inclusion of scientists and civilian personnel. This blog post covers why we have chosen a life history approach, lays out the benefits of life history interviewing for both participants and researchers, and provides an overview of our approach.

What is a life history interview?

The life history interview is a research method in which interviewees are asked to narrate their entire life story to an interviewer. It prioritises the narrator’s words and focuses on allowing the interviewee to structure and organise their narrative in the way that they wish to. [1] Most life history interviews are based on a schedule which might cover subjects such as childhood, education, employment, and health, but the method also requires flexibility in technique and structure.

Where oral history interviews usually focus on a specific event or period in a person’s life, the life history interview instead covers the entire lifetime. These interviews therefore can reveal not only ‘what people did’, but ‘what they wanted to do, what they believed they were doing, and what they now think they did’. [2] At their core, then, life history interviews record the entirety of the narrator’s experience in their own words, in the way that they wish to tell it, with the guidance of an interviewer. [3]

Why have we chosen a life history approach?

There are a number of reasons why the project has decided to take a life history approach to our interviews. We have outlined the main reasons below.

Subjectivity

Firstly, we are interested in learning about the impact that participating nuclear tests has had on the life course of veterans. Because life history narratives document the subjective experience of an individual – that is, the full complexity of their life, including their emotions, values, and beliefs – the approach offers a detailed insight into the complex consequences of test involvement and helps researchers understand this fully. [4] This is something which has, to date, been neglected in historical research on Britain’s nuclear tests.

Historical Context

Secondly, the life history narrative locates the story of the nuclear tests within a historical context of a life. [5] By allowing test veterans to tell us their entire life story, these narratives will show how participation in Britain’s testing programme fits into the broader history of post-war Britain and the experience of men living and working in this context.

Benefits for the Interviewee

The experience and process of producing a life history can also have benefits for the interviewee. Life histories can help individuals make sense of events and ‘put their lives in perspective’. [6] Indeed, in the interviews we have conducted so far, many veterans have commented that the experience of telling us their life story has felt cathartic and validating. It is hoped that by allowing veterans the chance to tell us their story in their own words, the project can offer a sense of validation and an opportunity to be listened to, while contributing to a significant piece of historical research which will be preserved by the British Library.

Project Outcomes

Finally, our choice of life history interviewing will help us to fulfil the project’s desired outcomes. The primary project outputs for An Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans are an online, publicly accessible database of life history interviews hosted by the British library, educational resources for schools, and a touring exhibition for the public. Storytelling and narrative construction are innate human communication tools, and as such, the presentation of nuclear test veterans’ narratives as whole life stories is suited to these public history outputs. When presenting historical events which are less well known among the public, such as the nuclear tests, the life history approach positions veterans’ narratives of nuclear testing within the lifespan of participants and thus situates the tests within more familiar facets of twentieth-century history, such as the experience of post-war national service, and relatable human experiences, such as coming-of-age, family life, and health. [7]

Our Approach

The project’s life history interviews will be broken into three sections, usually conducted over two or more sessions.

1. Early Life

2. The nuclear tests

3. Later Life

The interviews will proceed chronologically through the life story, covering these three phases of the veterans’ lives, but the direction, focus, and overall order of the narratives will be dictated by the veteran. Beginning with early life situates the life history within the context of childhood and youth, which provides a solid foundation for the continuation of the narrative. Similarly, separating the nuclear tests into a section allows a full exploration of this phase of a veterans’ life, while still ensuring that the interviewer and interviewee remain aware of this part of the life narrative as part of a broader “whole”. Ending with the experience of later life after the tests allows veterans to consider the impact that their involvement in the test has had on the rest of their lives, and enables the continuation of their life narrative up to the present day.

Notes

[1] Alessandro Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (eds.), The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 2015), p.54.

[2] Alessandro Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (eds.), The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 2015), p.52.

[3] Robert Atkinson, The Life Story Interview: 44 (Qualita8ve Research Methods) (London: Sage Publica9ons, Inc., 1998), p.8.

[4] Peter Jackson and Polly Russell, ‘Life History Interviewing’, in Dydia Delyser (ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualita8ve Geography, (London: Sage, 2010), p.179; Alessandro Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (eds.), The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 2015), p.52

[5] Annabel Faraday and Kenneth Plummer, ‘Doing Life Histories’, Sociological Review, vol.27, no. 4 (1979), p.777.

[6] Valerie Raleigh Yow, Recording Oral History: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists (London: Sage Publications, Inc., 1994), p.118.

[7] Annabel Faraday and Kenneth Plummer, ‘Doing Life Histories’, Sociological Review, vol.27, no. 4 (1979), p.778.

An Introduction

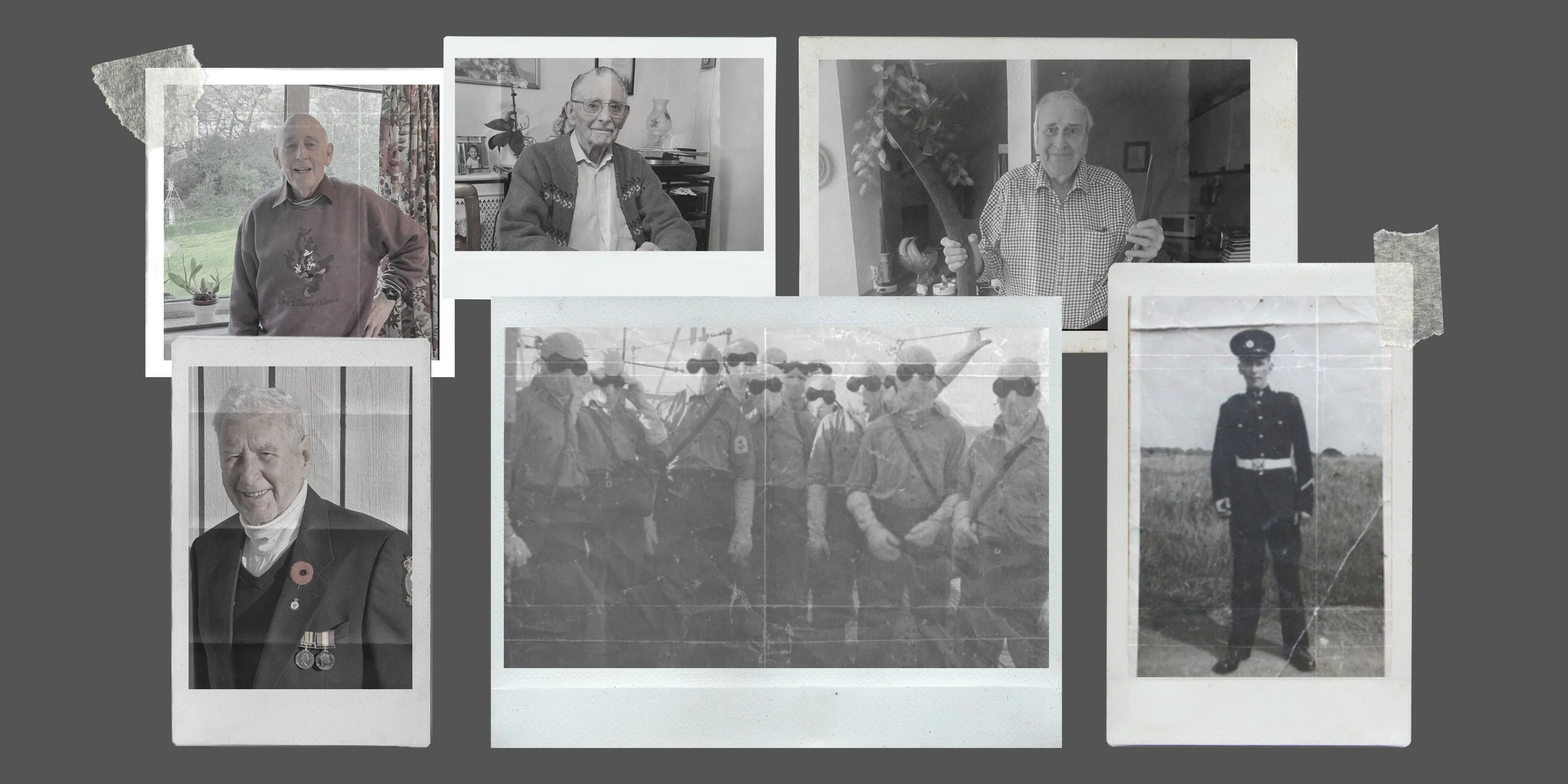

Gerry Bowler and fellow RAF servicemen on Christmas Island, 1957

Welcome to the new blog space for An Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans. We’ll be posting regular updates about our project, as well as sharing stories, photographs, and events.

We are a team of four from the University of South Wales and the University of Liverpool. This project aims to record oral history interviews with forty nuclear test veterans. We are working with the British Library and all of our interviews will be available via the British Library’s website for the public to listen to. The project is also making a short documentary film with film maker Sasha Snow, and preparing a variety of education materials for school to use to teach the history of the tests and their legacy.

Who We Are

Dr Christopher Hill

Our Principal Investigator, Dr Christopher Hill, is an Associate Professor in History at the University of South Wales. He recently undertook a project which explored the multifaceted role of imperialism across the cycle of nuclear development in Britain. His first book, Peace and Power in Cold War Britain explored the impact of media on democracy in modern Britain with a particular focus on the anti-nuclear movement.

Dr Jonathan Hogg

Our Co-Investigator, Dr Jonathan Hogg, is a social and cultural historian of the nuclear Cold War. He is a Senior Lecturer in Twentieth-Century History at the University of Liverpool and his book British Nuclear Culture helped establish nuclear culture studies as an influential field of research. He is currently also working on a number of edited collections, and is interested in exploring the life in 1980s nuclear Britain.

Dr Fiona Bowler

Dr Fiona Bowler is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of South Wales. She is a historian of twentieth-century Britain and an experienced oral historian. She is currently writing a book on the history of the British nuclear test veteran movement in the twentieth century, which will be published by Liverpool University Press in 2025. Her grandfather, Gerry Bowler, served on Christmas Island during Operation Grapple and witnessed four atmospheric nuclear tests.

Joshua Bushen

Our Research Assistant, Joshua Bushen, has just finished a Masters by Research in History at the University of South Wales. His thesis explored the experiences of servicemen during Operation Dominic, a US testing programme stationed on Christmas Island in the 1960s which was supported by approximately 300 British soldiers. He is experienced in conducting oral history interviews with veterans.