Life History Interviewing: An Overview

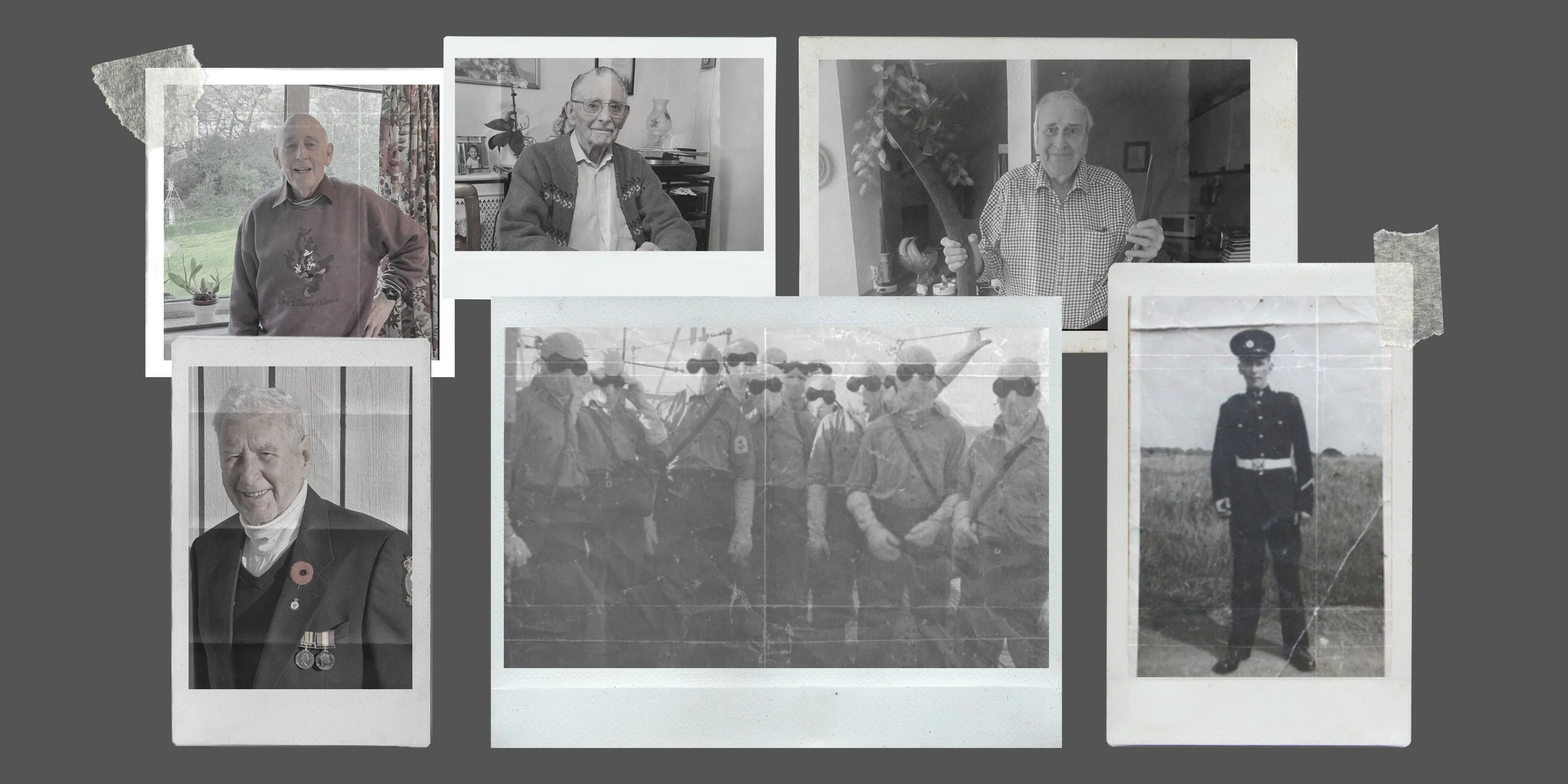

In conducting our oral history interviews, An Oral History of Nuclear Test Veterans will use a life history approach. We aim to conduct interviews with forty British nuclear test veterans, covering all major test operations and services, with the inclusion of scientists and civilian personnel. This blog post covers why we have chosen a life history approach, lays out the benefits of life history interviewing for both participants and researchers, and provides an overview of our approach.

What is a life history interview?

The life history interview is a research method in which interviewees are asked to narrate their entire life story to an interviewer. It prioritises the narrator’s words and focuses on allowing the interviewee to structure and organise their narrative in the way that they wish to. [1] Most life history interviews are based on a schedule which might cover subjects such as childhood, education, employment, and health, but the method also requires flexibility in technique and structure.

Where oral history interviews usually focus on a specific event or period in a person’s life, the life history interview instead covers the entire lifetime. These interviews therefore can reveal not only ‘what people did’, but ‘what they wanted to do, what they believed they were doing, and what they now think they did’. [2] At their core, then, life history interviews record the entirety of the narrator’s experience in their own words, in the way that they wish to tell it, with the guidance of an interviewer. [3]

Why have we chosen a life history approach?

There are a number of reasons why the project has decided to take a life history approach to our interviews. We have outlined the main reasons below.

Subjectivity

Firstly, we are interested in learning about the impact that participating nuclear tests has had on the life course of veterans. Because life history narratives document the subjective experience of an individual – that is, the full complexity of their life, including their emotions, values, and beliefs – the approach offers a detailed insight into the complex consequences of test involvement and helps researchers understand this fully. [4] This is something which has, to date, been neglected in historical research on Britain’s nuclear tests.

Historical Context

Secondly, the life history narrative locates the story of the nuclear tests within a historical context of a life. [5] By allowing test veterans to tell us their entire life story, these narratives will show how participation in Britain’s testing programme fits into the broader history of post-war Britain and the experience of men living and working in this context.

Benefits for the Interviewee

The experience and process of producing a life history can also have benefits for the interviewee. Life histories can help individuals make sense of events and ‘put their lives in perspective’. [6] Indeed, in the interviews we have conducted so far, many veterans have commented that the experience of telling us their life story has felt cathartic and validating. It is hoped that by allowing veterans the chance to tell us their story in their own words, the project can offer a sense of validation and an opportunity to be listened to, while contributing to a significant piece of historical research which will be preserved by the British Library.

Project Outcomes

Finally, our choice of life history interviewing will help us to fulfil the project’s desired outcomes. The primary project outputs for An Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans are an online, publicly accessible database of life history interviews hosted by the British library, educational resources for schools, and a touring exhibition for the public. Storytelling and narrative construction are innate human communication tools, and as such, the presentation of nuclear test veterans’ narratives as whole life stories is suited to these public history outputs. When presenting historical events which are less well known among the public, such as the nuclear tests, the life history approach positions veterans’ narratives of nuclear testing within the lifespan of participants and thus situates the tests within more familiar facets of twentieth-century history, such as the experience of post-war national service, and relatable human experiences, such as coming-of-age, family life, and health. [7]

Our Approach

The project’s life history interviews will be broken into three sections, usually conducted over two or more sessions.

1. Early Life

2. The nuclear tests

3. Later Life

The interviews will proceed chronologically through the life story, covering these three phases of the veterans’ lives, but the direction, focus, and overall order of the narratives will be dictated by the veteran. Beginning with early life situates the life history within the context of childhood and youth, which provides a solid foundation for the continuation of the narrative. Similarly, separating the nuclear tests into a section allows a full exploration of this phase of a veterans’ life, while still ensuring that the interviewer and interviewee remain aware of this part of the life narrative as part of a broader “whole”. Ending with the experience of later life after the tests allows veterans to consider the impact that their involvement in the test has had on the rest of their lives, and enables the continuation of their life narrative up to the present day.

Notes

[1] Alessandro Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (eds.), The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 2015), p.54.

[2] Alessandro Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (eds.), The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 2015), p.52.

[3] Robert Atkinson, The Life Story Interview: 44 (Qualita8ve Research Methods) (London: Sage Publica9ons, Inc., 1998), p.8.

[4] Peter Jackson and Polly Russell, ‘Life History Interviewing’, in Dydia Delyser (ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualita8ve Geography, (London: Sage, 2010), p.179; Alessandro Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (eds.), The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 2015), p.52

[5] Annabel Faraday and Kenneth Plummer, ‘Doing Life Histories’, Sociological Review, vol.27, no. 4 (1979), p.777.

[6] Valerie Raleigh Yow, Recording Oral History: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists (London: Sage Publications, Inc., 1994), p.118.

[7] Annabel Faraday and Kenneth Plummer, ‘Doing Life Histories’, Sociological Review, vol.27, no. 4 (1979), p.778.